The Value of Patient Experience Data

When conducted within the context of clinical trials, qualitative interviews can generate meaningful patient data to inform trial design and gain deeper understanding of the treatment experience and treatment benefit from the patient perspective. While there is growing interest among regulators, payers and pharma sponsors in conducting this type of patient experience interview, their value argues for wider use, especially in light of growing trends toward patient-centered research. In this post, experts from Evidera’s patient-centered research group — Carla Dias-Barbosa, senior research scientist, Mona Martin, vice president – science, and Miriam Kimel, senior research scientist — describe the types and terminology of qualitative interview studies, discuss their value in the research process and point to challenges and solutions in their conduct.

Why Conduct Patient Interviews?

During a recent webinar focused on best practices in collecting qualitative patient experience data as embedded interviews within clinical trials, we surveyed 155 attendees to take a snapshot of when and why they use qualitative interviews in their clinical studies. The good news: 32% said they had experience with qualitative research as a method of data collection. The not-so-good news: fewer than 10% of their clinical trials included this type of interview.

Qualitative patient interviews conducted within context of clinical trials can inform research processes and help sponsors build the value story for new therapies. Among our webinar attendees, the top reasons for conducting interviews were to inform interpretation of clinical outcome assessment (COA) results and measurement strategies for COAs in future trials, to explore patients’ trial experience and to understand treatment benefit. Their top reasons for not conducting interviews were thinking there would be extra burden on study subjects and sites, the complexity of interview timing and scheduling and the cost.

The wide range of research questions these studies can address — and the growing interest in patient input from regulators, payers and clinicians — argue for wider use of patient interviews. More knowledge and experience with this emerging field will help sponsors appreciate the benefits that make interview studies well worth the investment.

Mapping the Interview Landscape: Study Types, Timing and Designs

Various types of qualitative interviews can be used at different points in the research process, giving sponsors lots of choices and flexibility. As you plan interview studies, it’s important to consider the type of interview you want to implement, the research question you are pursuing and the timing as it relates to your study design.

Types of Interview Studies

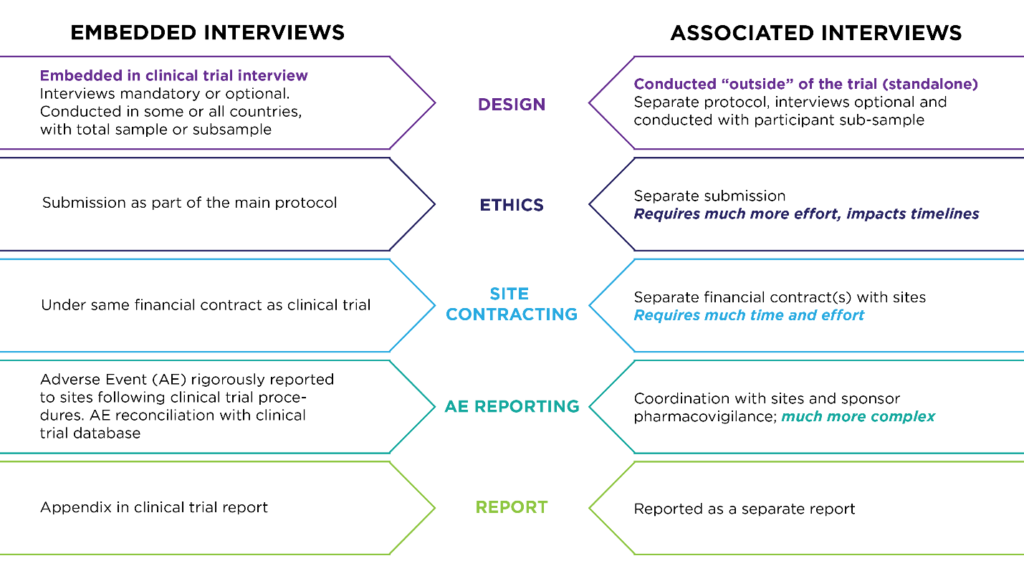

First consider what type of interview will be the most appropriate to answer your research questions. Although “exit interview” is a common designation, it is only one type of qualitative interview that refers to the timing of when it’s conducted (usually at the end of a treatment period). Exit interviews can be done as embedded interviews within a clinical trial. They can also be done as “associated” interviews with the clinical trial population but in a separated study after patients leave the clinical trial. Other types of interviews that can be embedded in clinical trials include feasibility interviews (to test a plan or assumption), cognitive interviews (to test content validity) and exploratory interviews (to describe something or define a problem).

Timing: Single or Longitudinal Interviews

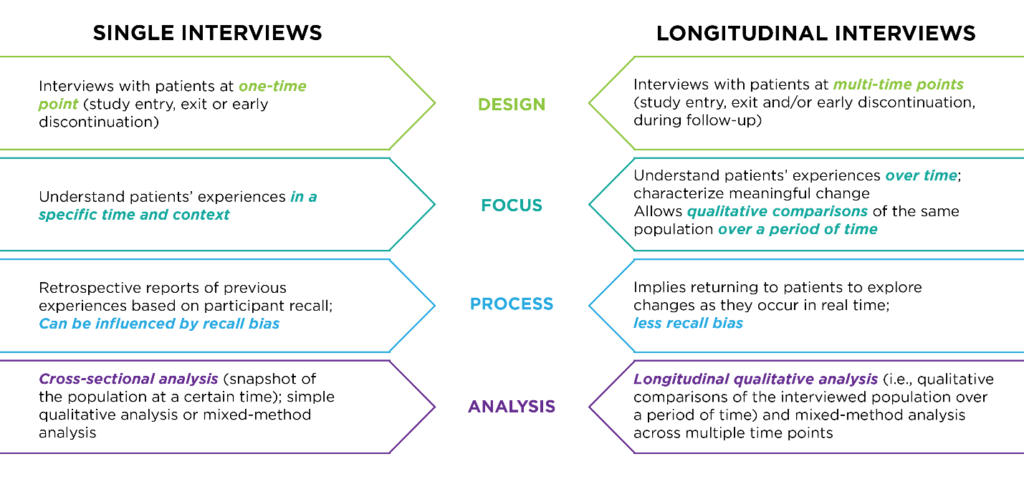

Your research objectives also determine the interview schedule. Single interviews — for example, one interview at screening, treatment initiation, end of treatment or study exit — are used to understand subject experience at a specific timepoint. Longitudinal interviews are conducted at multiple timepoints — for example, at study entrance, exit and during follow-up — to understand meaningful change in the subject experience over time.

Sample

Interviews can be conducted with the full subject population of the clinical trial or with a targeted subset of participants. When using subsets, sample diversity is important to consider against the clinical trial design. Cross-functional analysis, which assesses population experience at a given time, is appropriate for single interview designs. For designs that conduct interviews at multiple timepoints, longitudinal qualitative analysis is used to compare the interviewed population over a period of time. Mixed-method analysis, which combines interview data with clinical trial data, can be used for both single and longitudinal designs, as shown below.

Matching Interview Studies to Your Research Objectives

The type of interview — its timing, sample size and analysis — always depends on your research goals. The sample size can be small for content validity and cognition, or larger for descriptions of experiences with conditions, treatments and study designs. While subsets may reduce study burden overall, they must be considered carefully. It may be best to attempt to interview all study participants who agree and consent to interviews if experiences like treatment-related symptoms are being evaluated.

Challenges and Solutions: Plan Ahead, Train Thoroughly

Sponsors express concerns about the burden of patient interviews on clinical sites and study subjects. Additional complexity for operational teams is also high on sponsors’ list of reasons not to conduct interview studies. But, you can overcome many of these obstacles with appropriate interview approaches and three essentials: planning, training and education.

Reducing Site Burden

You can conduct these studies in ways that add very little burden to sites. Interviews should be conducted by skilled research staff experienced in qualitative interviewing rather than site staff. Qualitative interviews should be included as a formal part of study design during protocol development and should include site training, interviewer training and QC monitoring components.

Reducing Patient Burden

Sites are naturally protective of study subjects and may be reluctant to conduct “non-essential” tasks, especially when patients are ill. However, we find that patients often have a very different perspective, and interviews give them a way to talk about things that are important to them. More often than not, these interviews are a good experience for patients and support their engagement in the study. It’s helpful to patients to talk to someone who is interested in what they have to say and who won’t judge issues they want to voice. At the beginning of the study, patients should be helped to understand the importance of the interviews so they feel that they are being asked to contribute something of value. Site training should emphasize this point to help site staff balance the need to protect patients with the benefits of giving a place to the patients’ voice.

Timing Interviews

There is valid concern that the process of a qualitative interview might cause a subject to think differently about their experience. This risk is reduced when you conduct the interview close to the relevant treatment event or study visit but after other research questionnaires have been administered. Interviews should occur within a defined window of time, typically within 14-21 days of a scheduled visit or study event.

Training

Interviews embedded in global clinical trials face some special challenges, including managing interviews across different cultures and languages. Training must be documented and be specific to the study itself, as well as to the interview guide. Monitoring interview quality and consistency of coding should be planned for. The training must be well thought out ahead of time, standardized and documented.

The Patient Voice Improves Your Value Story: Stakeholders are Listening

Meaningful patient data can improve your value story with regulators and payers. Plan ahead to collect the right data to support adoption of your therapy in clinical practice. In early trial phases, patient interviews can increase understanding of the target disease and help characterize treatment benefits and safety profiles. In Phase II, for example, interview data can help clarify disease symptoms in terms of type and frequency of duration to support selection of study endpoints — especially useful in rare disease studies in which little is known about disease progression and patient experience of symptoms and impacts.

In Phase III, interview data can be used to identify meaningful change for a clinical outcome and support value messages based on direct patient input. Findings can be included directly in the patient experience section of the product label. In Phase IV, interviews can help to identity and explore long-term effects of treatment in real-world settings, including benefits, adverse effects and adherence over time.

Improving Value for Stakeholders

Payers can use these data to develop better value messages in terms of treatment benefit and patient satisfaction. For patients, interview data can help identify unmet medical needs that may be addressed in current or future clinical trials and help foster adoption of new treatments. Regulators can use interview data to interpret patient-reported outcome (PRO) scores and help define COAs. Potentially, patient experience data may improve understanding of overall balance in therapeutic benefits and adverse effects.

FDA Seeks Patient Perspectives

Regulators are more and more interested in patient input into the drug development process. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has released a series of four methodological guidance documents to facilitate systematic approaches to collection and apply meaningful patient and caregiver insights in clinical research and regulatory decision-making. Qualitative interviews, which the FDA terms “exit interviews,” are cited in the 2019 draft guidance describing methods to identify what is most important to patients. Interview data are being used in FDA reviews. In our survey of FDA drug application reviews between 1 January 2017 and 31 March 2020, we found that 12% included an evaluation of qualitative interview data.

Two Case Studies

Two recent interview studies — one using a mixed-methods approach and the other an embedded longitudinal design — demonstrate the value of these data in drug development and regulatory review.

The first example comes from a Phase III trial to evaluate a treatment for female sexual dysfunction. The FDA requested additional evidence to support the proposed definition of “meaningful benefit.” The sponsor also wanted to assess patient perceptions of treatment benefit and acceptance for using an autoinjector device. A mixed-methods analysis of data from 242 interviews and 80 in-depth telephone interviews demonstrated that 59% of patients in the treatment arm reported meaningful benefits compared to 27% taking placebo. Survey data was combined with clinical trial results to support a responder definition; findings were submitted to the FDA to support meaningful change definition.

In the second case, data from embedded longitudinal interviews helped inform National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines for treatment of women with heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB). There was little evidence to guide initial medical treatment for HMB; in 2017, NICE introduced guidelines for a first-line treatment, but this was based on limited evidence of cost-effectiveness from a single trial. To further evaluate clinical and cost effectiveness of the new therapy compared to the usual medical treatment, researchers conducted a pragmatic randomized trial with a longitudinal qualitative study. Interviews were conducted at two and 12 months after start of treatment. Findings supported the NICE guidelines and provided valuable practical information for women and primary care practitioners regarding treatment choices and expectations for medical treatment.

These and a wide range of other successful interview studies have taught us two essential lessons. First, think ahead. When you set out to capture the patient’s viewpoint in the course of your clinical trial, plan for your interview study well before the trial begins. Second, involve stakeholders early. Their interests will help you shape interview objectives and maximize the value of your findings.